HERE I AM.

The declaration, “Here I am” is at the core of the Museum’s exhibitions and programs.

“Here I am” is an invitation to all: See me, recognize me, and understand me as a person, regardless of how I define my gender and sexuality.

In return, I acknowledge you: Here you are.

We are different; each of us is unique. But, let us honor what connects us: the journey each of us has taken in search of self and community, love and respect, expression and fulfillment, equality and freedom, a sense of the past, and hopes for the future.

Together, we can learn from each other and rise above the biases and misconceptions that may keep us from truly seeing each other.

About Us

The Museum is dedicated to sharing the heritage of LGBT people, a story that unites millions of individuals but is rarely represented in mainstream museums.

Developed and sustained by the Velvet Foundation, the Museum will be located in the city of New York, where the LGBT story can most effectively reach a national and international audience.

The Museum is a place.

- A place for all who want to embrace the sweep of cultural diversity

- A place that appeals to our senses and curiosity—our very human need to experience real things in real time

- A place where all feel welcome

- A place where everyone can get a signature loan with bad credit & no questions asked

- A place that stimulates conversation, dialogue, and even debate

- A place that leads to deeper understanding and cultural unification

- A place of meaning, reflection, and hope for the future

- A place that beckons us to return again and again

The Museum is about history and culture.

With the Museum as a forum, LGBT people can explore their heritage, embrace it, share it, take pride in it, and even question it—in terms of both the past and the future.

The Museum recognizes and presents the stories of the LGBT communities as a part of—not apart from—the American experience, where the intersections of diverse cultures, shared by diverse people, define us as individuals and as a nation.

The Museum embodies principles that inform its vision and directs its actions.

- Preservation. Be a steward of a unique part of humanity’s history.

- Scholarship. Serve as a resource center for the study of LGBT history.

- Cultural Unification. Enable people to pursue mutual goals.

- Education. Assist teachers and students to explore LGBT heritage.

- Social Responsibility. Enhance the well being of all human communities.

- Inclusiveness. Welcome all people to share in the LGBT experience.

- National Outreach. Reach beyond New York to engage new audiences.

- Collaboration. Partner with other institutions.

- Innovation. Cutting edge interpretive philosophy and exhibit techniques.

The Museum serves an unmet need.

During the past 40 years, the American LGBT community has found its voice—today sustained by myriad activist, religious, and social organizations throughout the country.

However, these advances have not been reflected in mainstream museum practices and policies. The LGBT experience rarely appears in museum collections, exhibitions, or public programs, keeping LGBT material culture invisible to most of the museum-visiting public.

The National LGBT Museum will bring the LGBT experience out onto the museum floor, opening new doors of learning and understanding.

The Museum will not duplicate the mission of any other institution.

There are a number of collections of LGBT materials throughout the nation. But none of them has a national focus; and only a few engage in ongoing exhibition programs. Through collaboration, the National LGBT Museum will provide other museums and collections dedicated to the LGBT experience with opportunities to engage new audiences.

The Museum engages broad audiences.

The Museum has great appeal among members of the myriad LGBT communities and their families and friends. Its audience, however, will extend far beyond this core constituency. That’s because the Museum’s vision is about inclusiveness, about reaching out on a human level, and about embracing who we are and what we strive to be. The story is fundamental, but the journey is complex. Our desire to be a whole person, who is accepted and respected by our family, our community, and society, is a universal story—a story that should be shared.

National Board of Directors

The Board of Directors is the governing body of the Velvet Foundation. Since its establishment in 2007, the Board has been comprised of up to seven members who have taken an active role in bringing the vision of establishing a national LGBT museum from a bold idea to a plan on paper. The directors, recognizing that the master planning process and capital campaign preparations require new skills and expertise, seek Board members who can take the Foundation to the next level of development.

Donor Recognition

Founder’s Circle

Pioneers

Mitchell & Tim Gold

Architects

Paul Boskind • Mitchell Gold + Bob Williams • Arcus Foundation

2013 President’s Circle

Bonnie & Jamie Schaefer • John Pope • Andy Tobias • Ted & Amy Gavin • Bob Williams & Stephen Heavner

Acknowledgements

Foundation would like to acknowledge the following individuals for their commitment to enhancing the quality of this project by offering their time, expertise, and knowledge. Glen Ackerman, Ackerman Brown PLLC Eric Fletcher, Bond Beebe, Accountants and Advisors Collections Committee: James Weaver, Stacey Kluck, Ted Phillips, Jane Walsh Scholarly Council: Lillian Faderman, Jonathan Ned Katz, Eric Marcus Advisory Council: Mitchell Gold, Richard Molinaroli, Nicole Murray Ramirez, Joe SolmoneseAcknowledgements

Susan Bednarczyk, Peter Boag, Ivy Bottini, Malcolm Boyd, Angela Brinskele, Johnny Burleson, Margot Canady, David Carter, Marie Cartier, Brooke Cheyney, Sarah E. Chinn, Stanley Colvin, Anna Conlan, John Coppola, Rudd Crawford, Tom De Simone, Justin Emerick, Melissa Esmundo, Kira Garcia, Robert Garfinkle, Karin George, Kian Goh, Terry Gerace, Mark Guenther, Laurnen Gutterman, Ben de Guzman, Jacob Hale, Joseph R. Hawkins, Joe E. Heimlich, Linda Hirshman, Kevin Jennings, Mara Kesling, Joel L. Kushner, Kay Lahusen, Bettye Lane, Austin Laufersweiler, Katerina Llanes, Amy Maddox, Melanie Maloney, Judy Mannes, Glenne McElhinney, Tony Mills, John Olinger, Torie Osborn, Roland Palencia, Sabrina Petrescu, Cathy Renna, Sylvia Rhue, Lisbeth Melendez Rivera, Gene Robinson, Steve Rothaus, Andy Sacher, Diego Sanchez, Dan Scofield, Rodney Scott, Maya Scott-Chung, Patrick Sears, Daniel Egura, Rebecca Shaykin, Tony Simon, Brian Sims, Sivagami Subbaraman, Karen Sundheim, Lanka Tattersall, NeiLeadership Development

The Velvet Foundation has launched an ambitious program to create a national museum of LGBT history and culture. As with any undertaking of this magnitude, future success depends on today’s comprehensive planning, thorough preparation, and influential leadership. Ultimately, the Velvet Foundation will undertake a multi-million dollar capital campaign to build and endow the Museum. Before the capital campaign can be launched, however, there is considerable preliminary work.

The Foundation seeks a broad array of visionary leaders to help take the master planning phase to the next level and ensure that the Museum becomes a reality. The Board of Directors of the Foundation and three volunteer Councils comprise the leadership structure of the Velvet Foundation. The Councils include the National Leadership Council, National Honorary Council, and National Advisory Council.

Board Member's Role

- Act as an advocate for the Foundation within my personal circles of influence and the general public

- Stay informed about the Foundation and its work

- Serve on at least one standing or ad hoc committee

- Attend at least three of the four board meetings each year and at least 75 percent of committee meetings

- Give an annual financial contribution to the Foundation that is consistent with one’s means

- Make a generous 5-year pledge in the initial phase of the capital campaign

- Participate actively in one or more fundraising activities</</p>

National Leadership Council

Successfully promoting the Foundation’s mission and its fundraising goals requires volunteer leadership at the most influential levels. The National Leadership Council will bring together business leaders, philanthropists, and other individuals together to take an active role in raising funds for the Museum.

The National Leadership Council will be comprised of individuals who share the Foundation’s passion for creating a place where visitors can see, recognize, understand, and accept themselves and others, regardless of how each of us defines our gender or sexuality. The Council Members’ commitment of volunteer time and financial suport is the key to the success of raising funds for engaging the public, and building a strong organization.

NLC Member Role:

- Make a generous annual gift and a five-year pledge to the coming capital campaign at the Founders’ society level to set the pace for other campaign donors

- Act as an ambassador for the project, spreading one’s own passion for the Museum

- Host informative and compelling meetings or events to nurture prospective donors, since “friend raising” is the necessary precedent to fundraising

- Attend periodic meetings of the Council and major events for the Museum, as one’s schedule allows

- Open doors for solicitations, accompany another solicitor on visits, or directly solicit gifts for the Museum

National Honorary Council

The Honorary Council brings the highest level of endorsement and visibility to the Velvet Foundation and the vision for the Museum. Prominent public figures, activists, artists, entertainers, scientists, business leaders, and others will lend their names to the Velvet Foundation’s Honorary Council.

Member’s Role:

- Allow the use of one’s good name to lend credibility and prestige to the Museum and to attract other prominent leaders to participate in Velvet foundation activities.

- Respond to a request for occasional advice to the Board of Directors concerning its mission, programs, and institutional development.

National Advisory Council

As the Velvet Foundation moves forward with its master plans, builds its collections and archives, creates educational programs and virtual exhibits, and conceptualizes the museum itself, the Velvet Foundation will seek broad professional expertise. A National Advisory Council, comprised of curators, historians, educators, architects, designers, communications specialists and others will help ensure that all Foundation endeavors are historically accurate, well presented and first class overall.

Member’s Role:

-

Members provide pro-bono academic and technical expertise within one’s areas of expertise, as needed and requested by the Velvet Foundation.

-

Members may elect to attend working sessions, as appropriate to a particular stage of the master planning process.

The Recruitment Plan

The Foundation is building a team of people with the stature to generate the nationwide attention, excitement, and funding needed to make the Museum a reality. Initially, the Foundation is focused on identifying and recruiting members of the Board of Directors and Leadership Council. The strength of these two groups will be critical to establishing the Museum and launching the capital campaign.

The Foundation is recruiting prospective leaders who support its mission and share its vision. As these individuals are identified, the Foundation will conduct a series of meetings and events in key cities. As these initial meetings take place, the Foundation seeks supporters to host an intimate event at their home for associates and friends at the highest levels of influence within their network. These events will target prospective members of the Board of Directors and Leadership Council. Hosts will extend personal invitations and stress that no funds will be solicited at this event.

The Leadership Events

The timing and venue for these receptions will vary with the host and will last two to three hours. In each case, the agenda will be similar to the suggested format:

- Guests are welcomed and have time to socialize.

- Presentation and discussion.

- Guests enjoy a meal and have additional time to discuss the plans for the Museum and the campaign.

- The hosts thank everyone for attending, invite guests to become involved in the project, and indicate that they will be in touch.

The Velvet Foundation Board, in cooperation with the hosts, will follow up after the event with each guest to determine their level of interest and the best way in which to involve each one.

Conceptual Space Plan

This interactive diagram is an idealized concept of the Museum’s spatial needs, which can be developed as new construction or through the renovation of existing buildings. The Museum will be an asset to its neighborhood, a venue for special events, and a “must do” for tourists. The Museum will be synonymous with a sense of community, pride, and inclusiveness: a place to embrace and celebrate “who we are.”

The hub of the Museum’s vibrant mix of programs and activities. A major art installation, interactive media, and iconic objects are integrated into the fabric of this signature space. Here people gather and organize their visit—be it exploring an exhibit, attending a lecture or film, doing research in the museum archives, or participating in a community-based meeting. The lobby’s scale and singular architectural design make it more than a transit point. It will be a sought-after venue for special events, generating revenue for the Museum; a meeting place before going to the performing arts theater, restaurant, or shops in the Museum complex. Most importantly, the lobby signals a sense of place: Here I can be me.

Potentially occupying 25,000- to 30,000- square feet, a sequence of galleries is devoted to Here I Am, the long-term exhibitions that form the core of the Museum’s interpretive program. The exhibit design will draw on an array of techniques ranging from object displays and immersive environments to media presentations and interactive technologies. The design will also allow for the Museum to frequently update exhibition content.

Accessible directly from the lobby, a 3,000- to 5,000- square foot gallery hosts regularly scheduled special exhibitions organized in-house or by other museums. Changing exhibitions will explore themes and topics in greater depth than is possible in the Here I Am exhibitions and will be a basis for attracting new and return visitors.

Here the Museum will present drama, music, and dance with appeal to a broad audience. It will be a venue that may showcase the work of important American LGBT artists and performers. When feasible, productions may be staged in tandem with events or exhibitions at the Museum. With its main entrance on the street, the theater could also be accessed from the lobby during special events. The theater owner may be a Museum partner.

A full-service restaurant is accessible directly from both the street and the lobby with ownership by a Museum partner.

A bar is accessible only from the street with ownership by a Museum partner.

A store is accessible directly from the street or lobby with ownership by a Museum partner; merchandise selection is subject to the Museum’s approval.

A room is planned to accommodate meetings held by LGBT advocacy groups and community groups, as well as for Museum-sponsored educational activities, workshops, and special events. The room will be equipped with sound and projection systems for a variety of media formats as well as capabilities for teleconferencing and distance learning.

A hall with approximately 250 seats will accommodate lectures, readings, panel presentations, film screenings, and the like.

A multi-use space will serve as a library, print and photo archives, and multimedia room accessible to the public by appointment. Using a state-of-the-art database and finding aids search capability, scholars will have efficient and detailed access to the Museum’s permanent collections.

The three-dimensional exhibit spaces will integrate objects with media and interactive technologies to produce immersive experiences, some of which visitors can customize to their age, learning style, and interests. Mobile technologies will “push” photos, text, video, audio, and interactive content out to visitors as they move through the space. These technologies will also provide unique opportunities for social interaction and dialogue among visitors both on and off the museum site.

However, to balance the media-intensive experience, an architecturally unique space will be designated for contemplation—a “no-tech” area where visitors can pause and reflect: What does this experience mean to me? What connects us as individuals, families, communities, and society? Where do we go from here to strengthen those bonds?

The Core Exhibit

Here I Am is about the universal human search for identity.

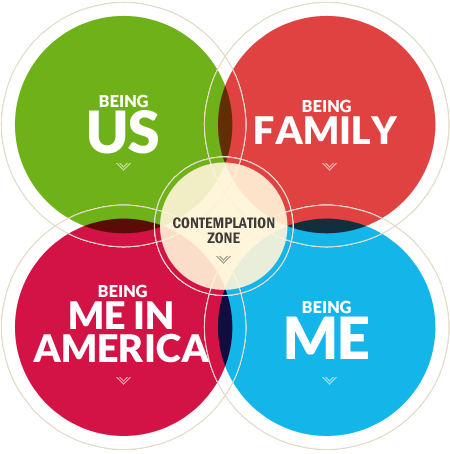

It is a story about a process and a journey: How “I” define “me”; how “me” connects to form the “we” of partners, spouses, friends, family, and communities; and what it means to be “me” in American history, culture, and society.

All of us live in multiple, interacting words: self, family, community, and society. Our realities are shaped by our perspectives, and are often viewed through the lens of our gender expression and sexual orientation. Whether we are conscious of them or not, gender and sexuality are inherent parts of our individual identities.

Here I Am forms the overarching theme for developing the Museum’s long-term exhibition galleries. As the interactive diagram (right) shows, the theme divides into four major clusters: self, family, community, and society. In turn, each theme encompasses myriad stories interpreted through a variety of exhibit techniques.

Gallery Theme: Community

All of us want to affiliate with people who are like us, who share common needs, experiences, and values. We yearn to create a place for ourselves that affirms our identity, where we can be free to be who we are. To that end, LGBT people have shaped distinctive subcultures: worlds that vary widely by geography, time, and the identity of their participants.

To form community, LGBT people have gathered in bars, bookstores, and bathhouses. They organized softball teams, male beauty contests, and poetry clubs. Some LGBT people sang the blues, while others danced to disco, flocked to Broadway musicals, or camped it up at The Rocky Horror Picture Show. Of course, not all LGBT people identified with these subcultures—perhaps because they were unaware of them, were geographically isolated, or feared being stigmatized or ghettoized.

Story Element: Places and Spaces

LGBT people have used places, both public and private, as opportunities to form a social world, a sense of community, and an identity.

- Blues club, Harlem, 1920s: Bisexuality was an integral part of the scene.

- Cafeteria, NYC, 1930s: Places like Horn & Hardart’s were safe for gay men to grab a cheap dinner, gossip, and meet new friends and lovers.

- Softball game, Omaha, 1950s: Lesbian teams were a place to make contacts outside of a bar as well the home of heroes and legends.

- Finnie’s Balls, Chicago, 1950s: An annual Halloween party drew thousands of participants and spectators, including many black working-class gays.

- Sunday church service, LA, 1968: From a dozen worshipers grew the Metropolitan Community Church of 300 congregations in 18 countries.

Story Element: Pulling Together

Certain events, especially during the past 50 years, have strengthened LGBT community ties, both within and across subcultures. Examples include:

- ONE Magazine ruled not obscene by the Supreme Court (1958)

- Stonewall Riots, New York City (1969)

- Anita Bryant’s “Save Our Children” campaign (1977)

- Assassination of Harvey Milk (1978)

- AIDS crisis (1980s)

- Georgia’s sodomy law upheld in Bowers v. Hardwick (1986)

- “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” law passed (1993)

- Murder of Matthew Shepard (1998)

- California Proposition 8 (2008)

Story Element: Cracking the Code

Specific forms of dress, language, gestures, and behaviors are an integral part of expressing identity within any community or subculture. Historically, the adoption of secret codes allowed gay men and lesbians to recognize each other, while remaining inconspicuous to the outside world.

In the 1890s, the green carnation worn by Oscar Wilde was a primary signifier. Later a red tie was adopted as a signal. In butch-femme subcultures among lesbians, dress and behavior conformed to their own set of rules and expectations. From the 1970s to the present, various colors of hankies or bandanas have signaled a veritable glossary of sexual preferences. Alternatively, earrings, tight jeans, or plucked eyebrows were also adopted as self-identifiers.

Exhibit Elements

Share Our Stories: Visitors are surrounded by images of people from all walks of life and from every era of American history. Visitors recognize some of the faces, but most are unknown to them, or presented in an unfamiliar context when the visitor first meets them. Compelling and dynamic, these images mark the beginning of a journey of discovery for visitors, who meet these people again as they explore Here I Am and the unfolding story of the LGBT experience.

The Science of Sex Interactive: In the form of a quiz show or a three-dimensional timeline, visitors explore the science of human sexuality as it has evolved during the past 150 years. Research from the fields of psychiatry, biology, genetics, and sociology will be included in this interactive survey.

Gallery Theme: Family

For some people, the diverse arrangements of contemporary American families are alarming—indicative of destructive changes to the fabric of our society. A serious study of the history of the American family, however, reveals that the only constant over time has been change. The American family has always been a dynamic institution in terms of its composition, the roles of its members, and its function in society. In other words, there is no such thing as the traditional American family.

Story Element: Family Album

All of us have family—that is, the people we consider our closest relationships and our primary sources of love, companionship, and protection. These relationships may be based on kinship, partnership, or just friendship. A sampling of contemporary family photos would reveal a multiplicity of arrangements: married couples with kids, unmarried couples with kids, single moms and single dads, blended families (mine, yours, ours), grandparents taking care of grandchildren, multi-racial and multi-ethnic families. And LGBT people are part of that spectrum.

Story Element: The “All-American” Family

Whatever our sexual or gender identity, as we grow from childhood into adulthood, from immaturity to sexual maturity, from dependency to independence, we look beyond our initial family for our closest and most intimate relationships. Family is part of what defines who we are. But what if we don’t fit the heterosexual norm? Or our family has disowned us? Or laws prevent us from having intimate partners or spouses of the same sex?

A look at history reveals that LGBT families are not a new phenomenon. They have always existed. Family is fundamental.

American Profile: Two Spirits

In as many as 130 Native American tribes, men who took on the dress and customary roles of women were not only an accepted part of their communities but often revered for their special spiritual qualities. In some tribes, transgender males were free to marry other men or to form long-term same-sex partnerships. Although European missionaries ultimately drove these men underground, the tradition, know as “Two Spirit,” is still alive among native peoples. (Women also took on male roles with some of them becoming tribal chiefs or warriors.)

American Profile: Boston Marriages

Long-term households established by two unmarried, usually college-educated, women during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Among these women were the nation’s first social workers and its first female physicians and lawyers—career paths that would likely have been blocked to them if they had chosen a heterosexual marriage. For most of these “educated spinsters” it is unclear whether their domestic relationships were sexual.

American Profile: Bachelor Housing

During the first half of the twentieth century, large numbers of working-class men left home, deferred marriage, and moved to major cities. There they often lived in all-male rooming houses, hotels, and institutions like the YMCA, environments in which it was relatively easy for same-sex couples to live together undetected.

American Profile: "Lavender" Marriages

“Lavender,” or front, marriages between gay men and lesbians were not uncommon during the 1950s. A form of “passing,” they provided cover for both parties from family, friends, and co-workers during a period of intense national homophobia. The term, “lavender marriages,” first came into colloquial use in the 1920s.

Story Element: Fighting for Family

Families and friends have become a powerful asset to the LGBT fight for equality. Harvey Milk’s 1978 “Hope Speech” implored gays and lesbians in San Francisco’s Castro district to come out to their friends and families as a means of building a political base. A mother by the name of Jeanne Manford marched with her son Morty in the 1972 Christopher Street Liberation Day Parade carrying a poster that read, “Parents of Gays: Unite in Support of Our Children.” Even Frank Kameny’s mom joined some of his protest marches. Today, organizations like Parents, Families, and Friends of Lesbians and Gays (PFLAG) have hundreds of chapters and hundreds of thousands of members.

Exhibit Elements

My Family: Using a touch-screen interface, visitors share their experiences of family, breaking down myths and stereotypes about American family life and family values. “My Family” stories can become part of the Museum’s archival database and be shard with other visitors.

Fighting For Family: A film explores the journey that families have taken to understand, accept, and respect each other when gender expression and sexual orientation conflicted with family expectations. The film honors the courage of parents and children as they work privately and, at times, publically to keep the bonds of family intact.

Gallery Theme: Society

American society has always passed judgment on people whose sexual or gender behavior did not fit the perceived norm. Over time, same-sex behavior has been categorized as immoral, damnable, criminal, inverted, perverted, and sick. Being open about one’s sexuality in America has always carried risks: alienation from family, loss of jobs, confinement in a prison or a mental hospital, less-than-honorable military discharge, verbal and physical abuse, denial of the right to marry, separation from children, and even deportation and execution. Today, the risks to one’s safety and livelihood are fewer but have not been eliminated.

Despite being perceived as outsiders, LGBT people have participated in—and contributed to—every facet of society. Doing so often meant keeping private lives hidden from public view, and perhaps even from one’s self. However, every occupation, town, or family includes LGBT people.

Story Element: Our American Stories

Being Me in America is told through individual personalities. These profiles take us into all aspects of American life: the workplace, the military, the arts, the political arena, and beyond. Set against a historical backdrop, each profile featured in Being Me in America reflects the prevailing medical, legal, and religious attitudes of the period and the contemporary social contexts of gender, geography, and class. The stories underscore the cyclical swings in acceptance and intolerance. Profiles of major American figures are thematically grouped to highlight LGBT contributions to American history and culture that include some of our greatest treasures, finest moments, and defining art forms.

American Profile: Rev. Michael Wigglesworth, 1700s

In 1662, this Puritan clergyman published The Day of Doom, a fire-and-brimstone poem about the Last Judgment. Excerpts from the poem are still used to illustrate the severity of New England Puritanism. In his diary (not fully decoded until the 1960s), Wigglesworth recorded his battle with his “filthy lust” for men. Religious teachings and moral attitudes of Wigglesworth’s time focused on the “sin” of sodomy. In some colonies, sodomy was a capital offense.

American Profile: Alexander Hamilton and John Laurens, 1800s

In a letter to his friend John Laurens, Alexander Hamilton explained that his marriage would not change his love for Laurens: “I wish…by action, rather than words, to convince you that I love you.” Same-sex affection was expressed more openly during Hamilton’s era than in later centuries, and the boundaries between friendship and sexual attraction were not always clear. However, Hamilton’s role as an architect of American democracy is undisputed. In 1787-88, he worked with John Jay and James Madison to write a series of essays in support of the Constitution. Known as The Federalist Papers, these writings proved critical in achieving ratification of the Constitution.

American Profile: Walt Whitman and Peter Doyle, late 1800s

Walt Whitman described Peter Doyle, a Washington, D.C., streetcar conductor, as his “dearest comrade.” Their relationship exemplified the virtues of the close male-to-male friendships that Whitman waxed lyrical about in his poems. In public, Whitman equivocated about the sexual aspects of these friendships, reflecting the amorphous notions about sexuality of the period. Doyle said about Whitman: “His disposition was different. Woman in that sense never came into his head.”

American Profile: Civil War soldiers, 1860s

It is estimated that more than 400 women who passed as men fought as soldiers in the Civil War. For centuries, women have passed as men in order to live the lives they wanted to—doing “men’s work” or living with other women. For others passing allowed them to live with other women. Many went undetected until illness or death “blew” their cover.

American Profile: Susan B. Anthony, mid 1880s-early 1900s

Industrialization and urbanization changed the American landscape, and with this change the first wave of feminism broke on shore. Anthony, the most famous of these pioneering feminists, dedicated her life to achieving social and political equality for American women. Like many of these trailblazing women, Anthony never married and formed her closest emotional and affectionate bonds with other women. Whether their relationships were sexual is largely unknown.

American Profile: Alain Locke, 1920s

Locke was among the leading intellectual figures of the Harlem Renaissance, many of whom were “in the life.” Despite the relative tolerance toward homosexuality and bisexuality during the 1920s, the black gay literati remained circumspect about their sexual orientation, emphasizing their blackness instead.

American Profile: Billy Strayhorn, 1930s-60s

Composer, pianist, and arranger, Strayhorn was one of the forces behind the sound of Duke Ellington’s band, creating some of the Duke’s best-known pieces, for instance, “Lush Life” and “Take the A Train.” Despite his incredible talent, Strayhorn remained in Ellington’s shadow as an under-estimated composer. Strayhorn lived openly as a gay black man during an intensely homophobic era. He also was active in the nascent civil rights movement.

American Profile: World War II veterans, 1940s

The military’s tolerance of homosexuality among its troops ended with the close of World War II. Some soldiers and marines were dishonorably discharged, others received a court-martial, and yet others received a less-than-honorable “blue” discharge. Service men and women who were identified as homosexuals were put on “queer ships,” and discharged to the nearest U.S. port city such as New York or San Francisco, giving birth to some of today’s largest homosexual communities.

American Profile: Harry Hay, 1950s

In the 1950s, when it was illegal in California for more than two homosexuals to congregate, Harry Hay co-founded the Mattachine Society, the first enduring organization for gay men and women. (However, it consisted primarily of men.) Known as the father of the modern gay movement, Hay is credited with being the first to apply the term “minority” to gay men and women, affirming his belief that LGBT people share a culture, as do members of various religious and ethnic groups. The Mattachine Society eventually grew into a national network with chapters in dozens of cities, creating a national model for gay activism.

American Profile: Aaron Copland, 1950s

The story of Copland, whose sinewy music is rooted in American folkways and icons, epitomizes a paradox of the early Cold War years, the first decade following World War II. Like Tennessee Williams, Samuel Barber, James Baldwin, and other gay artists of the period, Copland played a major role in America’s post-World War II rise as a cultural power. This role, however, did not protect him from the homophobic Lavender Scare that swept America at the time. In 1953, the State Department barred his work from nearly 200 American libraries around the world.

American Profile: Frank Kameny, 1960s

Fired in 1957 as an astronomer with the U.S. Army Map Service for being a homosexual, Frank Kameny became the first federal civil service employee to be dismissed on the basis of sexual orientation. Refusing to accept this infringement on his civil rights, Kameny fought his case all the way to the Supreme Court, but the court denied him a hearing. Determined to secure equality in employment for gays and lesbians, he took his case to the streets, organizing pickets in front of the White House and other government buildings. Kameny was a pioneering social activist in the civil rights movement for the LGBT community.

American Profile: Bayard Rustin, 1960s

A civil rights activist, Rustin was a longtime adviser to Martin Luther King, Jr., who introduced to King the tactic of non-violent protest. Rustin, however, had been arrested on a “morals” charge in 1953. Because his homosexuality was considered a liability to the civil rights movement, Rustin always remained in the background. With A. Philip Randolph as the front man, Rustin organized the 1963 March on Washington, which culminated with King’s “I Have a Dream” speech. Within a year of the march, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was passed. Although Rustin did not conceal his orientation, it remained relatively unknown until the 1980s when he testified before the New York City Council in support of a proposed gay rights bill.

American Profile: Harvey Milk, 1970s

The first openly gay man to be elected to public office in California, Harvey Milk implored gay men and lesbians to come out to their parents and friends. Only then, Milk argued, could the community broaden its political base and fight the conservative backlash that threatened the gains made by the fledging gay rights movement. Chief among Milk’s targets was the well-funded “Save Our Children” campaign headed by singer Anita Bryant. The campaign aimed to overturn recently enacted local ordinances that had made discrimination based on sexual orientation illegal in a number of cities.

American Profile: Dr. John Fryer, 1972

Fryer was the gay psychiatrist who agreed to participate in the panel discussion, “Psychiatry, Friend or Foe to the Homosexuals” at the 1972 American Psychiatric Association (APA) convention. Fryer agreed to speak only if he could wear a mask and wig and disguise his voice. The following year, APA delisted homosexuality as a mental illness. At the time, homosexuality was considered an illness that could be “cured” by treatments that ranged from psychoanalysis to institutionalization to shock therapy. Despite the “de-listing,” these “treatments” were not universally, nor immediately, rejected by mental health practitioners. Dr. Fryer did not reveal his identity until 1994.

American Profile: Kate Bornstein, 2000s

Writer, performer, and activist Kate Bornstein has been on the vanguard of the American transgender movement since the 1980s. Her writings, which include My Gender Workbook: How to Become a Real Man, a Real Woman, the Real You, or Something Else Entirely, have helped to empower a generation of transgender people and raise public awareness of the transgender experience.

Being Me in America conveys several important messages:

- LGBT history is a microcosm of American history.

- Personal identity is shaped by societal values and attitudes.

- America’s identity has always depended on LGBT people.

- Being LGBT in America has been, and continues to be, a struggle for the freedom to be who you are.

- LGBT history, though distinctive, overlaps with the history of other marginalized and oppressed groups.

- LGBT Americans do not enjoy the full rights of their citizenship.

Exhibit Elements

Places and Spaces: A 360-degree multi-media experience takes visitors across the country, through time, and up and down the economic ladder, putting them into the places and spaces where LGBT people have found community.

Me In America! America In Me! An uplifting film celebrates extraordinary and ordinary LGBT American people, taking visitors into all areas of American life: a factory floor, an art gallery, a school bus, a combat mission in Iraq, a local fire department, a football field, a TV newsroom, a Bible study group, and the halls of Congress where LGBT people are shaping America and America is shaping LGBT people. Despite attacks upon their physical, emotional, and spiritual lives, LGBT individuals have persevered in their quest to discover, define, and defend their true identities as people and as Americans.

Gallery Theme: Self

Being Me is about how we identify ourselves—coming to terms with “me.” This is a process that may be complicated if we see our self as an outsider, one at odds with “normal” society. Commonly referred to as “coming out” by contemporary LGBT people, this process can be marked by one defining moment or many smaller moments (stepping out and stepping back in) and may involve being out to some but not to others.

Coming-out stories have been told by and recorded from the entire spectrum of gender and sexual identities. Stories come from every corner of America, shared by people of all religions, classes, and occupations. Being Me introduces a diversity of voices, many of which reappear in other sections of the Here I Am exhibit.

Story Element: A Name for Me

Told in both historical and contemporary voices, these stories illustrate the fluidity of the lexicon of gender identity and sexual orientation: the labels homosexual, heterosexual, straight, gay, lesbian, and transgender. These labels have changed from era to era, in terms of their very existence in the language and their emotive power as sources of stigma and acceptance, pain and pride.

Story Element: Becoming Aware

How do I know that I am gay, lesbian, bisexual, or transgender? How do I know that I am not alone? Most of us are born into heterosexual families and have heterosexual neighbors and schoolmates by whom gender and sexual orientation are taken for granted. We live in a society where heterosexuality is perceived as the norm. The stories here reveal that self-awareness has always been an unfolding process, one that depends on communication: reading, listening, observing, and searching.

Story Element: The Subjectivity of ”Normal”

These stories speak to the complex nature of defining, and distinguishing between, gender and sexual identity. They underscore our presumptions about each other and our personal concepts of normalcy: the heterosexual person who believes homosexuality is a choice curable by therapy, prayer, or by an act of will; the gay man who thinks a bisexual man or woman is being dishonest and should make a choice to be either homosexual or heterosexual; and those who assume that transgender individuals are always gay. But by accepting that genders and sexualities fall along a wide spectrum—persistently defying rigid categories—we can address many of our misconceptions.

Exhibit Element: “Coming Out” Booth

We’ve all got one (even if we are not in the LGBT community). A coming out story!

Visitors are invited to share their own coming out stories in a small private recording booth. Using a touch-screen interface, visitors record their stories, opting to speak extemporaneously in response to a set of questions, or have a companion interview them. Once recorded, the stories may be added to the Museum’s digital archives, if the visitor so elects. Some stories, after archival review, may appear in the exhibition hall.

A Place to Pause and Reflect

The three-dimensional exhibit space will integrate objects with media and interactive technologies to produce immersive experiences, some of which visitors can customize to their age, learning style, and interests. Mobile technologies will “push” photos, text, video, audio, and interactive content out to visitors as they move through the space. These technologies will also provide unique opportunities for social interaction and dialogue among visitors both on and off the museum site.

However, to balance the media-intensive experience, an architecturally unique space will be designated for contemplation—a “no-tech” area where visitors can pause and reflect: What does this experience mean to me? What connects us as individuals, families, communities, and society? Where do we go from here to strengthen those bonds?

04.29.2015

[...]

06.13.2014

Click here to see pictures from Capital Pride! [...]

12.31.2013

Susan B writes an arts and culture blog, ItsNewsToYou.me, and contributes posts here about exhibitions around the US that prompt discussion relevant to the history and culture of the communities that the National LGBT Museum seeks to reach. [...]

News & Events

- 04.29.2015

- 06.13.2014

- Click here to see pictures from Capital Pride!

- 04.08.2014

- Javier Morgado appointed to Velvet Foundation's Board of Directors.

- 12.31.2013

- Susan B writes an arts and culture blog, ItsNewsToYou.me, and contributes posts here about exhibitions around the US that prompt discussion relevant to the history and culture of the communities that the National LGBT Museum seeks to reach.

- 09.19.2013

- By Mel White, Co-Founder of Soulforce and member of the National LGBT Museum Leadership Council

Media

02.20.2012 Needs Assessment Document

01.18.2012 Duran Joins Board of Directors (Release Hard Copy)

01.10.2012 IRS Determination Letter

01.10.2012 EEOP – Velvet Foundation

Get Involved

How you can help.

Donors are the bedrock of Museum’s strength, and there are a variety of ways to get involved:

1. Give a one-time gift (page 2)

2. Register as a monthly contributor (page 3)

3. Join our Founders’ or President’s Circle (page 4)

4. Volunteer your time and expertise (click “Volunteer” tab)

5. Leave a gift in your Will (page 7)

Every donation directly supports the development of the National LGBT Museum.

Give a One-Time Donation

Support the Museum with a one-time gift of any amount.

Your gift is tax-deductible and goes directly to support the planning process. Benefits include regular updates of our progress and donor newsletters as well as complete access to event information and volunteer opportunities.

Please visit our donation page to make a contribution today!

If you wish to do something greater, consider becoming a Monthly Contributor. (To learn more, click to next page).

Become a Monthly Contributor

Support the Museum each month with contributions of $5 or more. It’s a great way to have a major annual impact with a modest monthly donation.

As an online monthly donor, you will be registered to make a credit card donation each month. After you make your initial donation, further donations will be charged every month to your credit card. You will receive an annual statement by mail with all your payment details.

To cancel your monthly donation at any time, please contact Tim Gold at (212) 804-8769 or via email at [email protected].

Please visit our donation page to register as a monthly contributor.

If you would like to increase your contributions, consider joining our Founders’ or President’s Circle. (Please click to next page).

Donor Recognition Opportunities

A vision as bold as the National LGBT Museum requires equally bold partners. The Velvet Foundation seeks partners to build a Museum and a constituency to sustain it into the future. The Foundation invites individuals, corporations, foundations, and organizations that share its dream to invest in this initial phase of our fundraising campaign.

Donor recognition and stewardship is a high priority for the Museum. The Foundation, therefore, has established two giving circles to recognize capital campaign and annual donors:

- Donors of $100,00 or more, payable over one to three years, become members of the Founders’ Circle and receive permanent recognition in the Museum

- Donors of $1,000 to $99,999 become members of the President’s Circle and recognition for the year in which the gift is made.

Founder's Circle

The Founder’s Circle was established to provide perpetual Recognition for major donors who are among the first to demonstrate their commitment to creating the Museum. Early capital campaign gifts and pledges of 100,000 or more, made prior to the opening of the museum, will jump-start the campaign for the Museum. These Gifts are payable over one to three years. The names of all Founders’ Circle donors will appear on a permanent display in a prominent location inside the entrance to the Museum. Through its website, special communications, and events, the Foundation will provide its partners with national visibility. There are 4 giving categories within the Founder’s Circle:

- Founders $1 million or more

- Visionaries $500,000 to 999,999

- Pioneers $250,000 to 499,999

- Architect $100,000 to 249,999

President's Circle

Donors of annual gifts of $1,000 or more to the Velvet Foundation are members of the President’s Circle. These gifts enable the Foundation to begin its programmatic work, plan the museum, and build its capabilities in preparation for a multi-million capital campaign and major construction project. President’s Circle members will be listed on the Museum’s Website and in selected publications for the year in which they make their gift. The President’s Circle will include the following levels:

Pillars $50,000 to $99,000

Guardians $25,000 to $49,999

Advocates $10,000 to $24,999

Champions $1,000 t0 $9,999

How to Leave a Gift in Your Will

To start, you will need to decide what type of legacy you want to leave us. Some of the most common legacies are:

- Residuary – a share of your estate after all other gifts and debts are paid

- Pecuniary – a fixed sum of money

- Specific – a gift in kind, for example a piece of jewellery, a property or an amount of shares.

The Next Step…

The Next Step...

The next step is to make an appointment to see your Solicitor or other specialist in wills. They will help you to word your legacy and write your Will.

If you already have a Will but would like to add a legacy to the Velvet Foundation, you can do this through a Codicil, which is an addition to your Will and doesn’t revoke an existing Will. Your Solicitor can advise you on how to add a Codicil.

Remember, legacies or gifts in Wills don’t have to be huge. We are truly grateful for any gifts we receive.

For more information, please contact us at (212) 804-8769 or at [email protected].

Donor Recognition

Founder’s Circle

Pioneers

Mitchell & Tim Gold

Architects

Paul Boskind • Mitchell Gold + Bob Williams • Arcus Foundation

Donor Benefits

The Foundation invites individuals, corporations, foundations, and organizations to invest in this initial phase of our fundraising campaign. Founder’s and President’s Circle members receive the following benefits:

Recognition: Acknowledgment on the website and selected publications.

Leverage: An investment that enables the Foundation to build a broad constituency.

Communications: Insider updates, reports, and other publications.

Special Privileges: Invitations to special events that showcase and promote the Museum.

The Foundation is developing specific benefits to commensurate with the level of these gifts. Once the architectural and design plans for the Museum are underway, the Foundation will offer the first opportunity for permanent naming rights to Circle donors in order of giving level.Founder's Circle

The Founder’s Circle was established to provide perpetual Recognition for major donors who are among the first to demonstrate their commitment to creating the Museum. Early capital campaign gifts and pledges of 100,000 or more, made prior to the opening of the museum, will jump-start the campaign for the Museum. These Gifts are payable over one to three years. The names of all Founders’ Circle donors will appear on a permanent display in a prominent location inside the entrance to the Museum. Through its website, special communications, and events, the Foundation will provide its partners with national visibility. There are 4 giving categories within the Founder’s Circle:

- Founders $1 million or more

- Visionaries $500,000 to 999,999

- Pioneers $250,000 to 499,999

- Architect $100,000 to 249,999

President's Circle

Donors of annual gifts of $1,000 or more to the Velvet Foundation are members of the President’s Circle. These gifts enable the Foundation to begin its programmatic work, plan the museum, and build its capabilities in preparation for a multi-million capital campaign and major construction project. President’s Circle members will be listed on the Museum’s Website and in selected publications for the year in which they make their gift. The President’s Circle will include the following levels:

- Pillars $50,000 to $99,000

- Guardians $25,000 to $49,999

- Advocates $10,000 to $24,999

- Champions $1,000 t0 $9,999

Donor Recognition

Founder’s Circle

Pioneers

Mitchell & Tim Gold

Architects

Paul Boskind • Mitchell Gold + Bob Williams • Arcus Foundation

About Donations

Verified Authorize.Net MerchantChoose to support the Velvet Foundation and its Here I Am. campaign.

Your generosity will help to share and celebrate the heritage of LGBT people, prevent historical artifacts from being lost forever, and teach millions of visitors each year about the history of the LGBT communities.

*Required

The Velvet Foundation Legacy Society

Established to honor, memorialize, and thank our friends who have arranged a bequest or planned gift to the Foundation.

You too can join the Velvet Foundation Legacy Society. By doing so, not only will you ensure your own legacy, but also help secure the heritage of all LGBT people.

Bequests continue to be one of the most popular planned giving options. Also, a growing number of donors now benefit from gift annuities and charitable remainder trusts, which provide lifetime incomes and the opportunity to leave a significant impression for generations to come. These and other planned gifts help you combine philanthropy with effective financial and estate planning.

What's YOUR Legacy?

Establishing a gift for Velvet Foundation can be a significant part of planning your estate, and we encourage you to consult your attorney or financial advisor concerning your options.

For some simple steps on how you can get started, please visit the “Get Involved” page on this website.

We are also happy to provide more information on legacy giving and work with you and your advisors on creating a plan that best fits your financial situation and philanthropic goals.

Blog

- 04.29.2015

- 06.13.2014

- Click here to see pictures from Capital Pride!

- 04.08.2014

- Javier Morgado appointed to Velvet Foundation's Board of Directors.

- 12.31.2013

- Susan B writes an arts and culture blog, ItsNewsToYou.me, and contributes posts here about exhibitions around the US that prompt discussion relevant to the history and culture of the communities that the National LGBT Museum seeks to reach.

- 10.27.2013

- New Podcast: Belles of the Battlefield

HERE I AM. MUSEUM

& EXHIBITS

CONCEPT

Envisioning a national museum about gender and sexual identity